Jesus, I trust in You: The history and mystery of the Divine Mercy devotion

By Aaron Lambert

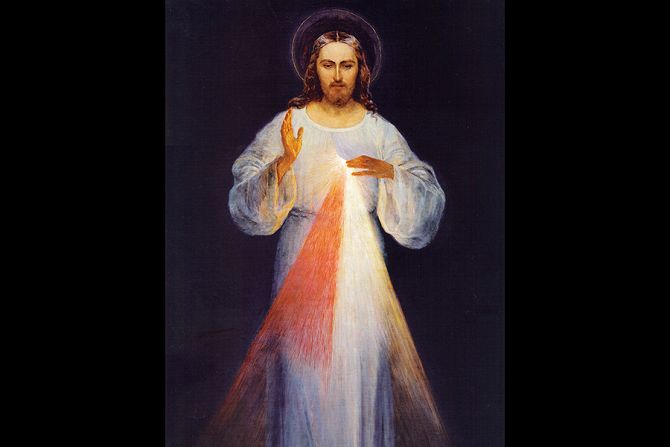

It’s one of the most recognizable sacred images from history, and it’s also one of the most mysterious. It adorns countless parishes and sacred spaces around the world and is the source of much devotion and adoration.

Tradition holds that the original Divine Mercy image was painted under the guidance of St. Faustina based on a mystical vision she had of Jesus. The image depicts Christ standing and looking downward with a compassionate and merciful gaze, His right hand raised, while His left hand holds His alb open at His chest as rays of red and white light radiate from His Sacred Heart. The words “Jesus, I Trust In You” are inscribed underneath — a signature for the painting that Jesus specifically told St. Faustina to include as she relayed to Polish artist Eugeniusz Kazimirowski how the image was to be rendered.

The history of the Divine Mercy image is as fascinating as the mystery of it, and the two are inextricably linked. Most of all, the image is reflective of a profound truth that Christ desired to communicate with the world prior to the outbreak of World War II in 1934 and a truth that He perpetually communicates through the image wherever it is venerated today.

The History

The humble origins of the Divine Mercy devotion originate with a poor and uneducated nun in Poland, St. Maria Faustina Kowalska. There was nothing particularly remarkable about this young woman, but Jesus chose her to communicate an important message of mercy from Him to the world.

On the night of Feb. 22, 1931, while St. Faustina was in her cell at the convent she was stationed at in Płock, Poland, Jesus appeared before her in a wondrous apparition. He was wearing a plain white garment with red and white rays emanating from His chest. As she recounts in her diary, St. Faustina received the following message from Jesus:

“Paint an image according to the pattern you see, with the signature: ‘Jesus, I trust in You.’ I desire that this image be venerated, first in your chapel, and then throughout the world. I promise that the soul that will venerate this image will not perish.”

St. Faustina was not an artist, but in 1933, when she was restationed to the town of Vilnius in what is now modern-day Lithuania, she was introduced to Kazimirowski by her confessor, Father Michael Sopoćko, and he painted the original image under the direction of St. Faustina and Father Sopoćko.

The painting was completed in 1934. On Good Friday in 1935, St. Faustina received further instruction from Jesus to dedicate the image and venerate it publicly on the Sunday after Easter. This marked the first time the image was revealed to the public.

A few months after the image was made available for public veneration, St. Faustina received another vision from Jesus, this time of the Divine Mercy chaplet, which is an equally important aspect of the Divine Mercy devotion. The Divine Mercy chaplet is routinely prayed at 3 p.m. by faithful all around the world in remembrance of Our Lord’s passion.

St. Faustina died from what is believed to be tuberculosis in 1938. Five years after her death, another rendition of the Divine Mercy image was painted by the Polish artist Adolf Hyła.That image resides in Krakow, while the original image can still be found in Vilnius today.

The Mystery

Daniel DiSilva, founder of the Original Divine Mercy Institute, has dedicated his life to uncovering the mystery surrounding the original Divine Mercy image and spreading its message around the world.

“I think it is as significant today as it was the day it was painted,” DiSilva said. “Maybe even more.”

While many commonly associate Divine Mercy with St. Faustina’s diary, DiSilva points out that Jesus never speaks about the diary to her, nor does Jesus make any promises to those who venerate the diary.

“A lot of people think that the diary is the biggest fruit of Divine Mercy, but Jesus didn’t come for the diary,” he said. “Jesus was not the one who asked her for the diary. He came for the painting.”

St. Faustina wrote the diary under the suggestion of Father Sopoćko, who thought it prudent for her to record her conversations with Jesus.

“There are no promises made to people who will read the diary,” DiSilva said. “There are only promises made to people who will venerate the image.”

As recounted in St. Faustina’s diary, Jesus makes several promises to those souls who venerate the image, pray the Divine Mercy chaplet and who honor and spread the worship of Divine Mercy, among others.

So what did Jesus desire to show the world through the Divine Mercy image?

“The message that Jesus is trying to communicate to the world through St. Faustina is in the painting,” DiSilva said. “There are details in this painting that reveal Divine Mercy. It doesn’t reveal mercy, and it doesn’t reveal divinity. It reveals Divine Mercy to the world through St. Faustina.”

While there are many aspects of Divine Mercy that the painting reveals, DiSilva shared three that are most significant. The first is that, as Jesus told St. Faustina, His mercy is unfathomable.

“In the painting, clearly, the rays that are emanating from Him are unfathomable, and that simply means they can’t be measured,” he said. “When we look at the original painting, and the original only, because the other paintings don’t have this, the mercy, which is represented by the rays, no one can see where they start, and no one can see where they end. They’re unmeasurable.”

Secondly, the painting shows that Divine Mercy is freely given.

“In the original image, Jesus is opening up His alb,” DiSilva explained. “In the other paintings of Divine Mercy, he’s simply pointing, or touching, at best. But in the original image, he’s lifting his alb, and he’s giving it. That’s Divine Mercy. God gives it. It’s not taken from Him. It is a giving. It’s a true gift.”

Third is the downward gaze from Jesus in the image, which is not one of the details that St. Faustina gave Kazimirowski as he was painting the image. That feature came from Jesus Himself.

“She didn’t give the direction for the downward gaze, but the downward gaze was there, and she asked Jesus, ‘Why, in the painting, are your eyes downward cast?’ And Jesus’ answer was, ‘My gaze in the painting is similar to my gaze from the cross,’” DiSilva said. “Only in the original masterpiece is His gaze downward. Why is it important? Because if He’s looking for us, He’s looking for us at the foot of the cross. That’s where we’re supposed to be to receive His mercy. And that’s a big deal.”

The Devotion

While the Divine Mercy devotion grew steadily in the years after St. Faustina’s death, it was after she was canonized and Divine Mercy Sunday was instituted by St. John Paul II in 2000 that awareness and practice of the devotion began to become more widespread.

In fact, it was St. John Paul II who advocated for the 1958 ban on the Divine Mercy devotion to be lifted. At the time, some Polish bishops were skeptical of St. Faustina’s claims and found the similarity between the red and white rays and the Polish flag to be concerning.

When the pope officially instituted Divine Mercy Sunday as an official liturgical celebration in the Church, it marked an important catalyst for the spread of the Divine Mercy devotion.

“I think it signified that starting now and going forward, mercy is going to be very important,” DiSilva said. “He obviously was the first Polish pope, and I think that it was a beautiful thing for Poland to have her elevated, especially after her writings and devotion to Divine Mercy were forbidden.”

Living the Divine Mercy devotion is transformative for those who strive to heed Jesus’ commands regarding it. Mercy lies at the heart of the Gospel, and as St. Faustina stressed, being merciful is something we should never grow tired of.

“She said, never be satisfied,” DiSilva said. “Wherever we are with mercy, with receiving, or giving or being merciful, we should never be satisfied. That’s the first step to being devoted to Divine Mercy, is to never be satisfied.”

Jesus intended for the Divine Mercy devotion to be a perpetual emanation of mercy from the hearts of His faithful. St. Faustina spent her life trying to convey this message in her time, as DiSilva is now. Jesus told St. Faustina that rays of mercy in the image represent blood and water, and as we pray in the Divine Mercy chaplet, they gush forth from Jesus as a fount of mercy for us. This fount is an inexhaustible stream that can always be accessed, so long as we place our trust in Jesus.

“Being merciful is not just an exterior, but an interior movement,” DiSilva concluded. “To be merciful, we have to do exactly what Jesus said when He put words in our mouth and said, I want the image accompanied by the quote, ‘Jesus I trust in you.’ That’s our signature. It’s not His signature. It’s ours, and we have to trust in Jesus.”

Aaron Lambert is a writer from Denver.